(Bloomberg) -- Egypt, the country hosting COP27 later this year, wants to ensure there’s no backtracking on past commitments to slow the pace of climate change — even as global leaders grapple with food shortages, an energy crisis and high inflation.

The annual United Nations-sponsored Conference of Parties is scheduled for November in the Red Sea resort city of Sharm el-Sheikh. Egyptian Foreign Affairs Minister Sameh Shoukry, who is also the conference’s president, spoke to Bloomberg News about the challenges ahead.

“The conference is going to be held in a difficult geo-political situation, with the world facing energy and food challenges,” he said in written answers to questions. “Of course all of this could impact the level of ambition and might lead to distractions of the climate change priority.”

Egypt’s goal is to prevent that from happening, Shoukry said. As the first African country to host a COP meeting in six years, it also wants to focus on how developing nations can get funding to adapt to the changing climate and to finance the green energy transition.

“We hope that COP27 will first confirm the political commitment to climate change and the agreed transition at the highest level,” he said. The main focus of COP27 is to “raise ambition” and confirm “no backsliding or backtracking on commitments and pledges” made in past summits, he said.

Thousands of climate diplomats representing virtually every country in the world meet every year at COP. The gathering also attracts tens of thousands of activists, observers, businesspeople and media, making it the world’s largest international summit by number of people. COP26 talks in Glasgow last year — the first to happen after the coronavirus pandemic — saw 40,000 people and 120 world leaders attending.

COP meetings are the vehicle through which the global community coordinates actions to cut planet-warming greenhouse-gas emissions. The ultimate goal is to cap the rise of global average temperatures which, at the moment, are headed for an increase of around 2.7°C or more by the end of the century, from the average of pre-industrial times.

Such an increase would be catastrophic, threatening life as we know it today, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The global community agreed at the COP21 meeting in Paris in 2015 to take steps to keep the temperature increase at 2°C, and ideally close to 1.5°C. The world has already warmed about 1.2°C, and the window to meet the Paris commitment is shrinking, Shoukry said.

“The science is clear and indicates that we are still not on track with regard to achieving the temperature goal, preparing for the adaptation challenges, or meeting the finance targets,” he said. “These gaps need to be bridged.”

But the global fight to tackle climate change is rubbing against a scramble for fossil fuels — including Egyptian natural gas — as Europe tries to move away from using Russian oil, gas and coal. That’s caused prices of natural gas to spike and led to a revival of coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, with countries burning whatever they can get their hands on.

“This is a major concern,” Shoukry said. “It is jeopardizing decarbonization and the energy transition.”

The plummeting cost of renewable power should lead to large investments into cleaner forms of energy, Shoukry said. But the current geopolitical situation suggests the switch to renewable power will take longer than the global community anticipated at the COP meeting in Glasgow last year, the minister said.

At the heart of the matter is how developing nations, and particularly African nations, implement this transition while making sure economic growth is not impacted. At Glasgow last year, poorer nations argued they shouldn’t be deprived of the opportunity to exploit their oil and gas reserves. Since then they have been stressing the priority of this year’s meeting should be on getting rich countries to pay more to help them transition to clean energy.

“It’s incumbent upon us to listen carefully to African concerns and to ensure that African priorities, such as adaptation and resilience,” Shoukry said. Adding that negotiations on finance should take into consideration “the needs of communities across Africa, who are suffering more than any other continent from the impacts of climate change.”

Europe’s rush to buy African natural gas, while lagging behind funding of green infrastructure and of gas pipelines and power plants has countries like Angola, Nigeria or Senegal hooked on dirtier fossil fuels and is delaying the access for hundreds of millions of people to electricity.

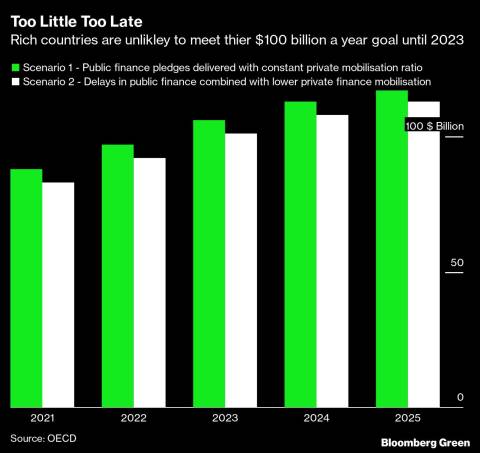

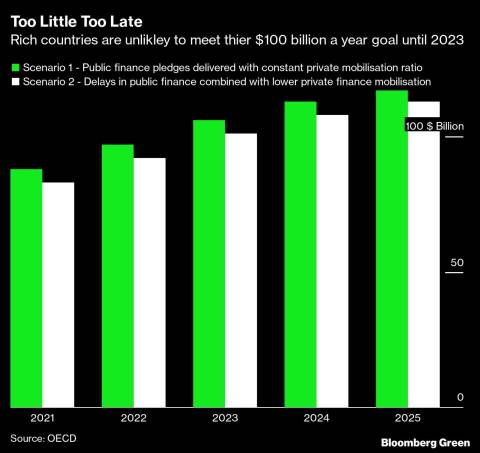

Under the Paris deal, developed countries agreed to provide about $100 billion annually by 2020. But they have fallen short by billions of dollars, with the new target to reach the sum by 2023. Shoukry wants COP27 to agree on further, increased sums transferred after 2025. The latest estimates to finance developing nations’ climate goals are in the scale of $6 trillion in total through 2030.

Getting there won’t be easy. Developing countries want the conversations about finance to not just remain on funding mitigation and adaptation to a warming planet. They want discussions also on what’s known in climate diplomacy jargon as “Loss and Damage.” That would mean developed countries, which are largely responsible for causing climate change, would need to compensate for some of the damage suffered by the poor, vulnerable countries.

It’s become a contentious issue especially in Africa, which is suffering the impacts of climate change more than any other continent. Meetings held earlier this year in Bonn to discuss technical issues leading to COP27 caused flare-ups between the two camps on Loss and Damage. The mood in a more recent meeting in Berlin provided more common ground.

“The job of the COP presidency is to align and converge the views and to overcome this divide,” Shoukry said. “Achieving a breakthrough in finance remains of high importance for many of the developing and African countries.”

Egypt is no stranger to this tension. The most populous Arab nation is highly vulnerable to climate change, with high temperatures and the salinization of the Nile Delta due to sea level rise impacting food production. Desertification is advancing in a country that lies mostly on hyper arid land, and the flow of the Nile river, which cuts through the country from south to north, is being impacted by a new massive dam in Ethiopia, further upstream.

The country was the first in the Middle East and North Africa to issue a sovereign green bond worth $750 million in 2020, tapping investors keen to fund clean transport, water supply for cities and the management of wastewater.

At the same time, Egypt submitted last month new and updated climate targets to the United Nations as part of its attempt to contribute to slowing the pace of climate change. The country will see its emissions from power generation rise 88 million tons in 2015 to 145 million tons in 2030. However, it is promising to keep the rise 33% below a business-as-usual increase. It also aims to double the share of renewables in the power mix to 42% by 2035. In June, the country also joined the Global Methane Pledge to cut emissions of the potent greenhouse gas by 30% by 2030. Egypt’s strategy includes planned investments of $211 billion for mitigation and $112 billion for adaptation, the minister said. The country needs a minimum of $196 billion to finance its updated mitigation target and $50 billion on adaptation by 2030.

The country’s plan does not include a target to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century, which is considered a gold standard for climate plans. The country’s first submission for a climate plan in 2015 was ranked “highly insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker, which provides independent scientific analysis of government climate plans. The non-profit is still analyzing the latest document, its website said. Plans by neighbor Saudi Arabia and large emitters China and India also rated as “highly insufficient” by CAT.

Shoukry would not confirm whether Egypt is planning to set a net-zero goal and referred to the government’s National Strategy for Climate Change 2050, which was launched last May and doesn’t include an emissions reduction target.

In the past, pressure from climate activists in protests across the world and at the conference itself have been essential to build pressure on negotiators. COP protests inside and outside the main venue have become a fixture, often staging colorful demonstrations that bring music, inflatable animals and dance to a conference that’s otherwise famous for the technicality of the talks.

That element is under question in Egypt, where unauthorized protests are banned and the government retains the right to cancel or postpone any demonstrations.

“While we recognize that governments play a central role for the success of international efforts to deal with the ‘climate crisis’, the current challenge requires the concerted efforts of all stakeholders,” Shoukry said when asked about whether protests will be allowed at Sharm el-Sheikh. “All stakeholders have to have a role at the COP, and the appropriate space to express their views at both the formal and the informal tracks.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

Author: Salma El Wardany, Laura Millan Lombrana and Akshat Rathi